Do We Need New Clans?

Vladimir Krasilnikov, Senior Game Designer

How did games come into our world? Our current knowledge on the history of games and playful behaviour suggests that this type of activity has been around for an incredibly long time – even before the appearance of mankind. Having observed the behaviour of animals, we can assume that games in their very beginning served as a tool of education and socialisation. While computer games are made by people for other people's enjoyment, they still use age-old triggers to awaken interest – the opportunity to learn, the curiosity surrounding something new, and the satisfaction of playing with those you love. This piece is centered around the latter.

I will use The Trail, a mobile game designed by 22cans (a studio headed by industry legend Peter Molyneux), as a primer to socialisation in games.

The Trail is a game about the frontier, survival and discovery - it is also a project that has stirred some controversy. The project looked intriguing before its launch, promising to carve out a new niche - “run-and-craft” - in the well-established world of mobile free-to-play. The miracle didn’t happen - on December 19th, the game was 177th in the US free iPhone apps chart, proceeding to fall off the radar completely. Botched implementation (The Trail manages to glitch even on the most powerful smartphones) and some rash decisions in its’ design seem to have done the game no favours. Errors aside, the game is quite interesting when it comes to players’ socialisation - but we’ll get to that later.

A brief history of social gaming

At the outset, in the era of arcade and PC games, playing against or with another player was the only available format. AI was taking time to develop, and rivalry between players didn't really need encouragement – you only need to recall the old “I reached the 9th speed in Tetris” to get an idea of what I'm referring to. “Hot seat” and “2-player mode”, which brought me so many tears of resentment and joy as a child, came about precisely around this time.

With the gradual expansion of networks, multiplayer games started springing up (I deliberately refrain from citing dates, as computer networks developed at different speeds in different regions, but we can generally say that this took place around 1975-1995). The first precursors to the MMO genre – text-based MUD (Multi-User Dungeon) games – took hold. Gameplay was sessional, as nothing else was possible at the time. The interface was also rudimentary: a description of the location, players and NPCs, and a console to punch in commands were all that were needed. Many MUDs had bulti-in online chats, offering players the first opportunity to communicate with opponents in other locations.

The rise of MMORPG (1996-1997) took the world by storm – social games began turning a profit. MUDs were incredibly difficult to monetise, as opponents were abundant and the game was fairly easy to make. MMORPGs, however, could not be free by definition, as they were centered around a graphical user interface – a rather expensive matter. The first popular MMORPG, Ultima Online, got 100,000 subscribers for a monthly fee of $10 within the first six months of its release. For at least a decade, MMORPGs became a holy grail for developers, as more users were willing to pay $10 every 5 months instead of $50 once. Everyone tried to create an online world in which they could live – and some succeeded! I personally know several people whose lives were changed by MMO: one friend married a girl from his clan, and another dropped out of college because he couldn’t tear himself away from gaming.

To this day, a clan’s acceptance of a new player in many MMOs is still treated as seriously as a job application

Addictions to online games also became a hot topic in the press. There couldn’t be more proof that social mechanics were important to retain players - people’s lives literally started revolving around games.

With the gradual accession of free-to-play to the top of the market food chain, MMO games changed yet again - subscriptions and DLC releases stopped working as a primary monetisation method. Instead, game designers focused on a freemium model offering exclusive gaming content, which often drew negative reactions (pay 2 win). The temptation, however, was too great. At this point, it was already clear that the clan segment of the audience contained the most engaged players. They were described as very competitive, and ready to invest a lot of effort and money into the game, so as to raise their clan in the rankings. As such, the upper investment boundary practically vanished – clans could pay as much as they wanted. In fact, clans fund all players in rivalry-based online games - something they do very eagerly.

Social networks gave online games new tricks – now you can use competitive and cooperative incentives to lure in people outside the gaming audience. What I’m referring to here are viral posts, something that a lot of people still hate (for no good reason, really – any modern social network lets you filter your feed).

What’s more important, however, is that online games now have the opportunity to build in a social context, even for players that don’t have it. For example, when you complete a level on “Match 3”, you can automatically see the results of your friends who also passed this level. At the same time, it doesn’t even matter if your friend actually completed that level – the game has access to his avatar and his name through the social network, and that replaces a faceless robot with a person you know. This doesn’t only help personalise the competition, but it lowers the entry threshold: “if my friend’s already playing this game, then he’s gotta know that I beat him on points!”.

Mobile games have built on the the opportunities offered by social networks. The latter, meanwhile, realised pretty quickly that they had given apps too much power – the madness that you could create with posts, invitations and requests from the game damaged the network’s reputation. Networks responded accordingly – Facebook, for instance, hid all game-related notifications as deep as it could. With the onset of mobile devices, however, apps gained access to a new stream of personal information: your contacts, messenger chats etc. The chance of missing a notification from your friends is also much lower nowadays, as people have their phone with them at all times

To tick or not to tick?

As such, developers are trying to make players in their games socialise earlier, easier and more often. The main technical difficulties were overcome by the first MMOs – the f2p era proved that socialisation was one of the most important aspects of player attraction and retention. Social networks and “smart” technologies are trying to remove the psychological barriers of socialisation (“Why do I need this?”, “My friend’s won’t appreciate this”, “I don’t know anyone in the game”, etc.).

However, even in those games, where clan dynamics are the main socialising tool, providing its participants with unique content and gameplay, joining a clan isn’t a default scenario

If you look at modern games, you may notice that joining a clan is much easier than it was in the old days of the first MMOs (back then they were called guilds). Retrospectively, it seems like a logical continuation: socialising was an optional aspect for a very long time. But should we always follow these “logical continuations” when making game design-related decisions?

Today there are genres where PvP and cooperative gaming are no longer additional functions – on the contrary, player interaction here lies at the gameplay’s core. Why do game designers still avoid clan dynamics as a way of ensuring the game’s progress (?) … One of the possible answers is that carefully made, deliberate decisions are perceived by people as their own, as opposed to decisions made for them. This answer is incomplete, however – people only choose to make important decisions for themselves, opting “not to choose” in all other cases.

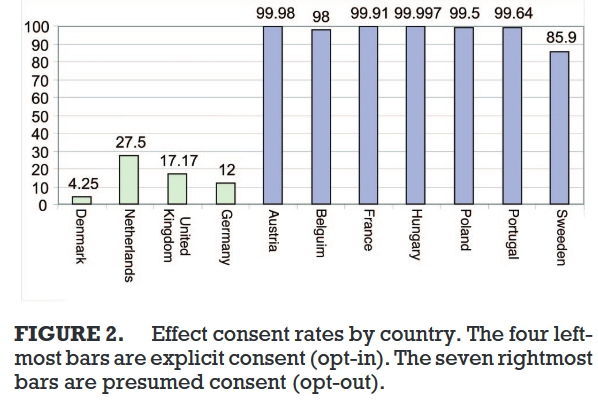

Original chart available at the following link.

A well-known study on organ donation by Johnson and Goldstein (2004) illustrates this. Countries in which people explicitly consent are located on the left, while countries in which people’s consent is presumed are located on the right.

The Road to Eden

Perhaps Peter Molyneux thought something similar when working on The Trail (or perhaps not). The game begins on the banks of a new settler’s world. A friendly guide introduces you to the game’s basic mechanics and controls. The trail calls on you to go forth – you only have to walk 14 kilometers to the city of Eden Falls. When we reach it, the city will be known as anything but Eden Falls. Because the city is in fact a clan, with its name chosen by the founding player.

From the game’s very beginning, our goal is to reach the social part of the game. Of course, we interact with other players before it, exchanging remarks on the trail and trading goods at road stops (allegedly these are “other” players – remember the virtual molds for NPCs?). What’s most important is that the game’s entire setting, goals and vocabulary convince the player that he’s right at home, exactly where he should be – the game translates and blends this in so eloquently that when you get to the city, you have no doubts or back thoughts about entering it. Compare this to your standard “get X coins to join clan” quest.

The Trail, however, fails to follow up this powerful initial impulse. The city rotates around filling the player’s box with tradable goods. Filled boxes are shipped to merchants, for which the city receives gold bullion in return, which it can spend on new buildings. The first item you put in a box defines its type – all the following items need to be the same as the first. Experienced players put in commonly found objects, such as pebbles, so that every resident can help fill the box quicker. If the first item is a set of intricately crafted pants, for instance, the likelihood of the box filling up gets close to 0, and you’ll have to wait a day for the box to emptied to start again.

One of the main challenges for the city’s residents in the game’s current version is domestic theft – intruders coming in and stealing stuff off people’s shelves. Perhaps the shelf was initially thought to be a place of exchange, so it was made available to all citizens. However, there’s no indication that this is the case, and the setting expectations (frontier, people’s harsh tempers, “my home is my castle”, that sort of thing) appear to have worked against the game mechanics. Even an “impenetrable” locked chest doesn’t seem to help.

As a result, people come home to empty shelves – ones that were full when they left the house. What follows is a reaction similar to that of the first farming games, where it was possible to expropriate other people’s property. To avoid wrong perceptions about these “public shelves”, a brief learning demo had to be built-in upon arrival in the city.

Afterword

Unfortunately, there aren’t that many multiplayer games that so elegantly solve the problem of joining a clan. There are probably more effective solutions in other games that I don’t know of. One the whole, The Trail’s stats aren’t that impressive, and it can hardly be used as a successful example: ThinkGaming gives an estimate of 12,000 installs and 16,000 USD generated per day.

More than anything, this article is a call to rethink the mechanisms of socialisation – not because the current ones don’t work, far from it, but because utilising clans laterally to the main gameplay is a tribute to tradition rather than a modern solution.

Other news

Epic War Robots 10th Anniversary is here!

April 24Along with lore-expanding cinematic

VentureBeat on War Robots' 10 years history and successes

April 23Interview with our executive producer

The Success of War Robots in Germany and its road to China

April 23Interview with GamesMarkt